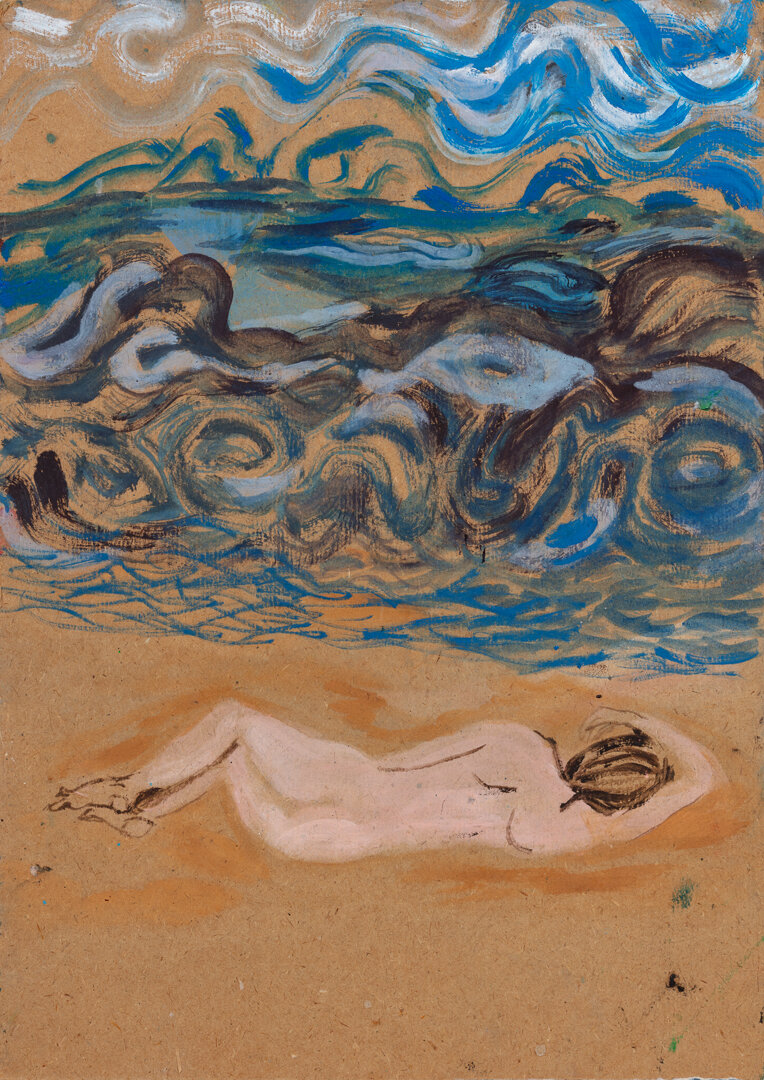

Dorothea Stiegemann, Untitled, 2015. Oil on canvas, 35 x 27 cm.

Dorothea Stiegemann

Eden

4th September - 20th November 2021

CLICK HERE to order the exhibition catalogue

This is not a religious exhibition. It does not have a story to tell, nor lessons to teach, and no moralities to impart. In fact, the burden of history and dogma conjured up at the mention of the Christian paradise is almost the antithesis of this presentation, where the works studiously elude a narrative, and have nothing to do with the Bible. Yet, after looking at the paintings, we have chosen to title this exhibition Eden, in spite of its connotational weight. This is because, together and alone, these paintings do each have at their heart a sense of longing for something lost, a yearning for a place that is ideal and innocent, before and beyond the complexities of man. That they are persistently defeated in this endeavour is what makes them human, honest and real. This is actually an exhibition about the impossibility of Eden.

Dorothea Stiegemann was born in Gießen, Germany, in 1983, and now lives and works in Berlin. She graduated from the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf, where she studied for almost a decade, initially under Jörg Immendorff and, later, as a Master’s student of Peter Doig. The inevitable challenge has been for Stiegemann to find her own position between those giants, a long and at times tortuous process that has in the end made this presentation possible.

Painted at various times over the past decade, these works describe a position that has not stayed still, but which can as a whole be said to be intimate, emotive and mysterious, and one in which paintings are led by two things: the artist’s compulsion, and the specific qualities of their materials, which here include oil paint, watercolour, ink and charcoal applied to canvas, paper and linen. This impulse towards objectivity over narrative makes the beguiling images at the centre of the works into elusive, poetic objects, objects that have been pursued through intuition and feeling more than blind dedication to their starting point.

For example, the first and, due to the nature of our space, final work of the exhibition, Untitled (DS1), began in reference to the triangular divisions of space and plane in The Piano Lesson by Henri Matisse (1916). It has however quickly spun away from that work, first by exchanging its grey-green palette for one of Mediterranean pinks and azures, and by moving the image from an interior to an exterior, so that the divisions no longer confine and instead thrust out, as though we are looking not at a living room but the sea. Likewise, Stiegemann’s idiosyncratic painterly touch, which looks like it has been applied with a feather rather than a brush, has led to the foliage-like agglomeration at the work’s centre (essentially an abstraction), that stands in direct contrast to the architectonic spatial planes taken from Matisse. It has become a painting that pits nature against architecture, lightness against rigidity, and perspectival depth against the flatness of the picture plane, a theatre of opposites that keeps the eye unbalanced and searching. It is, I think, a masterful picture, and one that leaves me longing for the South.

In a similar vein, the nude figures, flowers and landscapes that appear throughout this exhibition are motifs that could be said to have been taken from the canon of images of Eden. They are the motifs that have always been used to make visual the idea. However, what we see in Stiegemann’s paintings is never just an image of a figure, a bed of flowers or a landscape, but also a documentary of the artist’s process of failing to find a oneness with these things.

A work like Untitled (DS2), for example, could in the context of this exhibition be taken for a painting of Adam, or at least of man at peace in nature, reclining and untroubled in the verdant landscape of paradise. Even his blurred out face could be read as a sign of his pre-identity, his nameless, prelapsarian oneness with the world before there are other men. But look again: the body is shaky, its limbs stunted, the legs almost seeping into their surroundings, which elsewhere spill over and into him. For all the elegance of the initial image it is also a soggy, sodden, dripping paradise, not just a blissful idyll. These elements of trouble, these disturbances to the image, pull us relentlessly away from Eden.

Similarly, we can look at a work like Untitled (DS5) and see a world before the ravages of man, but we can also see a landscape that is bleak and drained, where trees and shrubberies struggle to find root, and where nothing quite feels whole. And in Untitled (DS24), we are not just given a dancer twirling happily in the blue, but a burning Icarus, a dancer that looks more like Masaccio’s Expulsion than one frolicking amongst the clouds.

In a series of recent works (DS8-14), the artist set out to make a group of small paintings of flowers that were not kitsch or sentimental, and that each approximated some sensation that can be physically experienced in nature: lying down in fresh wet grass, for example, or the smell of reddening leaves in autumn. That somewhat innocent endeavour is, again, troubled in every work, first by the fact that the paintings are at least as sickly as they are pretty, and by their spinning further and further away from the intended sensation as the act of painting took over: flowers become mere smudges and stains, canvases are rotated to look less and less like flowers, more like landscapes or abstracts, in every case disrupted. Beneath their elegance they are some of the more cynical paintings of flowers I have seen, more Fleurs du Mal than flowers of Eden.

In 2019 the artist gave birth to a son, whose tousled, cherubic head of hair appears several times in this exhibition, at first asleep and later morphing into the pulsing red petals of a flower in full bloom. I mention this because I found it so telling to hear the artist once say that she wanted to make paintings that show her son a better version of this world, one that might not exist for real but which can be reached for in the process of painting. I think that is a noble pursuit, one that here in the real world we could do with having more of. Eden, too, is not a place that can be reached, and certainly not held on to, but in the free space of art, we can try.

Dorothea Stiegemann, 'Untitled', 2014, Oil on linen, 135 x 140 cm

Dorothea Steigemann, 'Untitled', 2017, Charcoal on linen, 47 x 47 cm

Dorothea Stiegemann, 'Untitled', 2009. Oil on carton, 35 x 27 cm

L-R: 1. Untitled, 2014. Oil on linen, 135 x 140 cm. 2. Untitled, 2009. Oil on carton, 35 x 25 cm.

Untitled, 2017. Charcoal on linen, 47 x 47 cm.

L-R: 1. Untitled, 2021. Oil on linen, 40 x 30 cm. 2. Untitled, 2017. Watercolour on paper, 42 x 30 cm. 3. Untitled, 2014. Watercolour on paper, 40 x 30 cm. 4. Untitled, 2014. Watercolour on paper, 40 x 30 cm.

Avery, 2021. Watercolour on canvas, 40 x 50 cm.

L-R: 1. Untitled, 2012. Oil on linen, 179 x 134 cm. 2. Untitled, 2021. Watercolour on linen, 40 x 30 cm.

Pointy Elbow, 2013. Oil on linen, 40 x 30 cm.

L-R: 1. Blumenköpfe, 2021. Oil on linen, 40 x 30 cm. 2. Untitled, 2015. Oil on canvas, 35 x 27 cm. 3. Untitled, 2015. Oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm.

Untitled, 2015. Oil on canvas, 35 x 27 cm.

Untitled, 2017. Ink on paper, 30 x 42 cm.

Untitled (Avery), 2020. Watercolour on paper, 21 x 29 cm.

L-R: 1. Untitled, 2014. Oil on linen, 135 x 140 cm. 2. Untitled, 2009. Oil on carton, 35 x 25 cm. 3. Untitled, 2012. Oil on canvas, 179 x 134 cm.