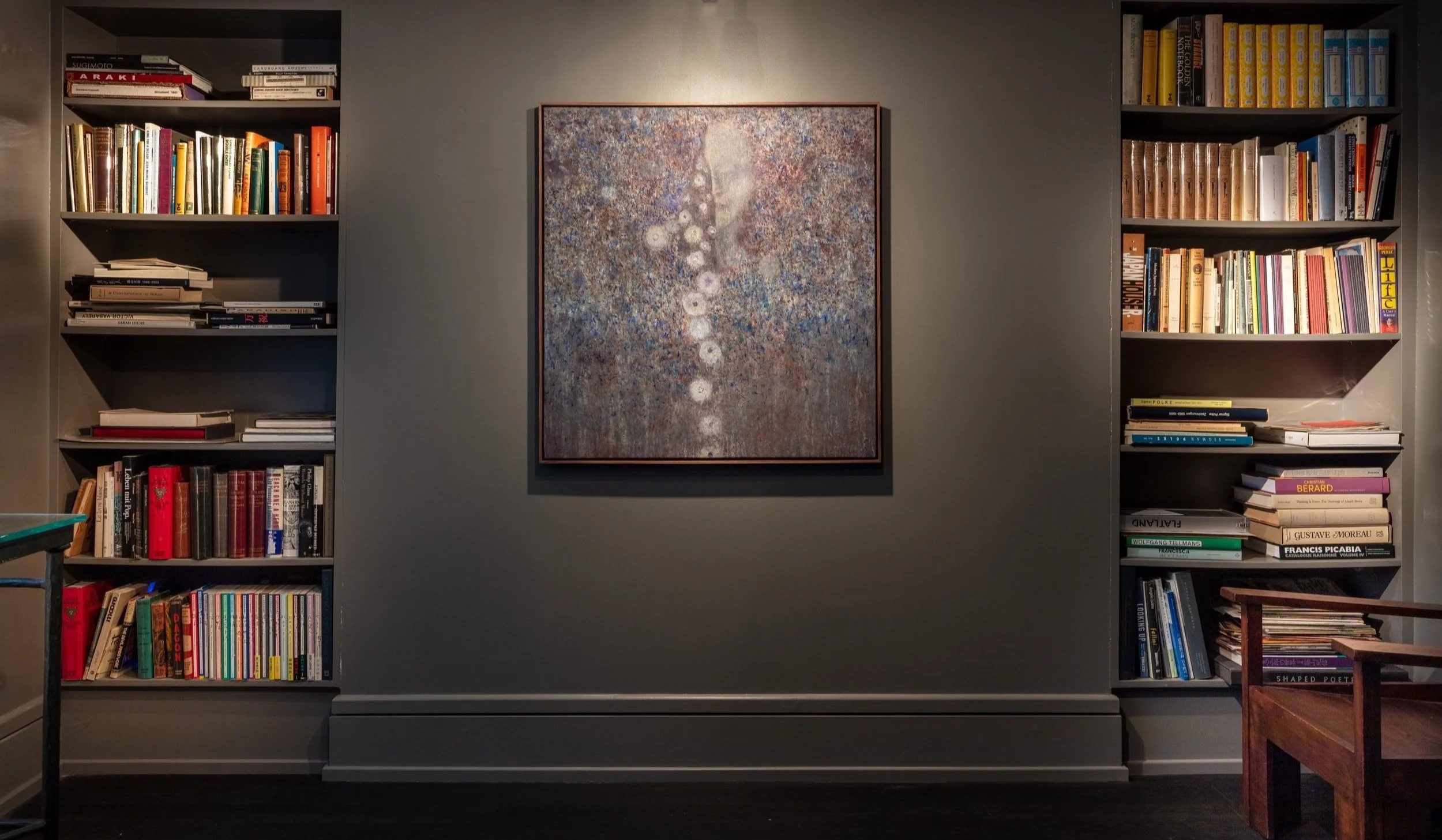

Oliver Bak, Orfeus, 2023. Oil and wax on linen, 91 x 86 cm.

Something Rotten

Oliver Bak, Katrine Bobek, Morten Knudsen, Anton Munar, Bertil Osorio, Marie Rosenzweig, Alberte Westergaard

11th January - 24th February 2024

CLICK HERE to request a digital copy of the exhibition catalogue

For a long time I have been interested in the idea of groups in Contemporary art. This is in part because I grew up in London in the 1990s, when the so-called YBAs held court, and those exhibitions are among the earliest I can remember seeing. The YBAs never had much in common with each other artistically, but they were connected by their biographical proximity, in other words, that they happened to be studying and/ or living in the same place at the same time, and it was useful for their dealers to call them a group for marketing purposes. It doesn’t matter if that sounds like a cynical strategy, because however disparate their work happened to be they still said something together about the state of Contemporary art in Britain at the time, they formed a shape around something at the heart of it. The need for the kind of manifesto-waving movements of the rest of the 20th century was gone: now everything is permissible, all the old rules have been broken down, rebuilt and reimagined for the individual, who can freely stake out their artistic position with whatever means they like.

One of the effects of this is that group exhibitions are quite often disastrous, particularly when the works are brought together around some theme or other curatorial conceit. Each artist will relate to the theme on their own terms, with cacophonous results, each voice singing from its own hymn book. But what I think can be interesting is to bring together a group in the same way as the YBAs were brought together, by virtue of their mere proximity, their connection thus being factual and established through friendship rather than practice, because then they might together form the outline of some aspect of the art being made in one place at a particular time. This has been the strategy employed in bringing this exhibition together - these seven artists are a group of friends, most of them having studied and most of them still living in the Danish city of Copenhagen.

Each of the seven was asked to contribute one or two paintings to the presentation, and no further instruction was given. Most kept painting right up to the shipping deadline, and all refused to share images of their works with me while they were still in progress, so I had no idea what this exhibition would look like, just some faith to go forward blindly. Now that they have safely arrived in London and at last I have them all before me, I wonder what do these things say when they sing together, what is the shape they make in Contemporary Danish painting?

While there are many more discrepancies than there are commonalities, there is at least one clarity that emerges. Perhaps it is more a sensibility than a strategy, a feeling more than a position. The best way I can find to describe it is that there is always something a little bit rotten in each of their paintings.

For example, there are several paintings of nature here, but it is never a fully contented Arcadia. There is always some death-figure lurking beneath the trees (Munar), or some sickly heaviness to the blue air and atmosphere (Bobek). When Bak or Westergaard or Knudsen paint flowers, they are not really joyous expressions of the bounty of life but rather expressions of death - their petals are treated as though they are viscera, meat-flesh going old and stale. Bertil Osorio’s summer barbecue looks like an alien invasion, his car park a desolate apocalypse, and the exquisite pair of coppers by Marie Rosenzweig, for all their charm and dance-like swapping, have each at their centre these blank black holes, these shadows where something is missing. Likewise, every painter here has in each their own way taken great pleasure in making their surfaces rich and painterly, celebrating the touch of their brush and the effect it produces on their support, but it feels to me like a fragile pleasure, a sensuality that is here just now but is at risk of being lost or taken.

While this group is looking as much to German painting and, even more, the French painting of the late 19th century, as they are to anything Danish, it is interesting to note the echo of this sensibility in the works of Danish painters historically. Per Kirkeby for one, the geologist-painter, looms large over this group, and further back Vilhelm Hammershoi and L. A. Ring, painters who twisted a precious sensuality into works that are slightly discomforting. And while this group is looking back they are also looking forward, to a world that is arguably losing its sense of touch, its capacity for authentic physical experience, and where nature and the natural world is quite literally under threat. That these seven are looking back to a moment in painting characterised by a comparable sentiment, the threat to the senses and the natural world that took place during the Industrial Revolution, is surely not a coincidence.

I very much hope that this will be just the first time that this group is brought together in an exhibition. I would like to see the same happen again, only bigger, with more artists showing larger works in larger numbers, and with more physical space between them. This ‘something rotten’ I am failing to describe is merely one aspect of the shape they are forming, and on a larger scale we might see the full complexity of the outline this group is making. But even in this small gallery, in these mostly intimate paintings, paintings that were conceived independently by artists whose primary connection is their friendship, I do feel as though something coherent has been said, and that it is beautiful, yes, lush and painterly and natural, but that it is also a beauty that is close to death, where the smell of the flowers is tainted, where the shadow of omens is foreboding.

There is an old Zen story about a man who is chased through the forest by a tiger, and who ends up hanging off the edge of a cliff clutching to a fragile vine. To his dismay he realises that another tiger is prowling in the ravine beneath him, and that a mouse has begun to nibble at the branch from which he is hanging. Just at that moment he notices a strawberry growing out of a crack in the cliff. Surrounded on all sides by death, he plucks the strawberry and pops it into his mouth. And it is the most sumptuous, perfect, delicious strawberry he has ever tasted.

Alberte Westergaard, 'In Blue', 2023. Oil on cotton, 62 x 36 cm

Bertil Osorio, 'Parking Lot Pastimes', 2023. Oil on canvas, 15 x 30 cm.

Morten Knudsen, 'when the sun is not enough', 2023. Oil, pencil, wax, foamboard in artist’s frame, 71 x 71 cm.

Katrine Bobek, 'Over the Hill', 2022. Oil on canvas, 38 x 24 cm.

Marie Rosenzweig, 'Fox', 2023. Shellac, oil, wax and chalk on copper plate, 14 x 10 cm.

Anton Munar, 'Tumbado y creciendo - lying down and growing'. Oil on found wooden drawer, 51 x 26 cm.

Oliver Bak, 'Orfeus', 2023. Oil and wax on linen, 91 x 86 cm.